Julian Cope and co.'s second is an overlooked classic... The Teardrop Explodes were victims of one of pop’s weirdest years. Their leader, Julian Cope, began 1981 as unlikely pop beefcake, vying with Simon Le Bon and David Sylvian for the hearts and wallets of a new glammed-up teen audience after the huge January success of the blaring, brass-driven “Reward” single. Then, while Cope, guitarist Troy Tate and drummer Gary Dwyer toured America, and entered George Martin’s Air Studios to make their second album, British pop went gloriously nuts. The Specials had hit No.1 with an Arabic reggae protest song that soundtracked the Summer’s riots. What followed was not more of the same, but a lurch into archly synthetic escapism, care of new romantics, synth-poppers, white disco and gender-bending. Meanwhile, U2 and Echo And The Bunnymen, the latter led by Cope’s former bandmate and bitter rival Ian McCulloch, were quickly finding a way to transform post-punk’s anti-macho anxiety into a new kind of arena rock. By the time the Teardrop Explodes released Wilder in November, their record-collector mix of Beatles and Love-quoting ‘60s psych, discreet funk and military brass sounded like four bookish hippies on magic mushrooms adrift in a nightclub full of narcissistic peacocks on ecstasy. Wilder bombed spectacularly and The Teardrops Explodes never made another album. Of course, Wilder’s commercial failure never made it a bad record. This is its second reissue – the first was in 2000 – and Cope’s long journey from pop eccentric to modern antiquarian and national treasure has only increased the cult cachet of his first magnificent failure of a band. But it’s still some shock to rediscover just how great, brave and strange Wilder sounds now, mercifully free of the desperation to cross over that even post-punk puritans like Scritti Politti and Gang Of Four fell for at the time. Wilder’s melodies sound timeless and deliciously free of conventional logic. Its rhythms, inspired by the returning David Balfe’s love of David Byrne and Brian Eno, reject straight time for adventures in syncopation and globe-trotting experiment. Its lyrics – packed with in-jokes about the Liverpool scene, Ian McCulloch’s sister, and Cope, McCulloch and Pete Wylie’s legendary six-week band The Crucial Three – are full of dark winks and unlikely connections between Palestinian freedom fighters and characters from David Copperfield… and that’s just within the prowling, spooked “Like Leila Khaled Said”. “Bent Out Of Shape”, “Passionate Friend” and “Colours Fly Away” are flawed but fabulous attempts to cemulate “Reward”. “Tiny Children” and “The Great Dominions” are the show-stopping ballads, Cope at his man-child best on the latter, somehow making the “Mummy, I’ve been fighting again” refrain poignant rather than pathetic, as Balfe’s Prophet 5 synth percussion throbs ominously beneath him. Conflict and breakdown are the album’s themes, as Cope’s band, drug-addled brain and first marriage were collapsing simultaneously. But Cope is quintessentially English, so the mood is stoic, playful, self-mocking. In poptastic 1981, Wilder made little sense. In 2013, where the musical landscape is full of well-read Dirty Projectors and Wild Beasts and Vampire Weekends, artily fusing psychedelic mindsets and world music motifs, the Teardrop Explodes’ final album sounds entirely contemporary and reveals itself as way ahead of its time. But the clincher is its embrace of the sadness of ending things, and our knowledge that Cope would leave Liverpool and The Teardrop Explodes far behind and go on to bigger adventures. “I could make a meal/Of this wonderful despair I feel”, Cope croons, soft and throaty, on “Tiny Children”. Wilder does exactly that, and then swallows, belches and looks to the future. Extras: Excellent second disc comprising B-sides, the final, posthumous “You Disappear From View” EP (most of which also appeared on the 2000 reissue), and BBC sessions. Plus revealing, self-deprecating sleevenotes from Messrs Tate, Balfe and Cope. 7/10 Garry Mulholland Q&A David Balfe Were the Wilder sessions as acid-fried as legend insists? No! Acid was hovering in the background and influencing a certain adventurousness. But you can’t live your life on it. In your sleevenotes for the reissue you state that Wilder isn’t as good as debut album Kilimanjaro. Why? We were trying to fuck about with things and throw funk in with trumpets and cinematic concepts of music, and I don’t know whether we pulled it off. I went on to spend the next twenty years being an A&R man (Balfe mentored Blur and was the subject of “Country House”) and I look at a song like “Bent Out Of Shape” in terms of adding this and taking away that and it could’ve been a big hit single. Is it true that you locked Julian Cope and Gary Dwyer out of the sessions for the third album? Or that Dwyer chased you through the grounds of Rockfield Studios with a loaded shotgun? No. One of the things Julian does – which I admire enormously – is mythologise everything. Julian has always been adamant that The Teardrop Explodes will never reform. Is this a good thing? I think he’s totally right. The part of me that would love to get onstage and play those songs with me old mates would quite like to do it. But I do admire Julian’s integrity. .

Julian Cope and co.’s second is an overlooked classic…

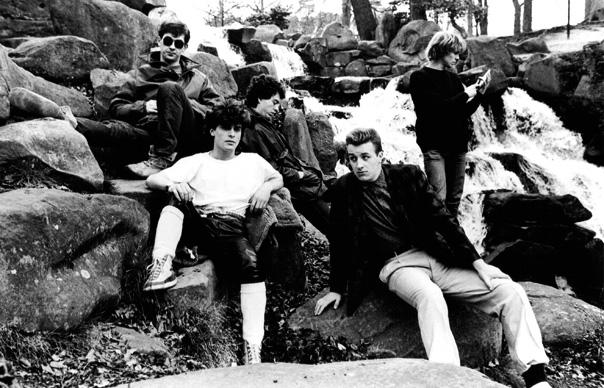

The Teardrop Explodes were victims of one of pop’s weirdest years. Their leader, Julian Cope, began 1981 as unlikely pop beefcake, vying with Simon Le Bon and David Sylvian for the hearts and wallets of a new glammed-up teen audience after the huge January success of the blaring, brass-driven “Reward” single. Then, while Cope, guitarist Troy Tate and drummer Gary Dwyer toured America, and entered George Martin’s Air Studios to make their second album, British pop went gloriously nuts.

The Specials had hit No.1 with an Arabic reggae protest song that soundtracked the Summer’s riots. What followed was not more of the same, but a lurch into archly synthetic escapism, care of new romantics, synth-poppers, white disco and gender-bending. Meanwhile, U2 and Echo And The Bunnymen, the latter led by Cope’s former bandmate and bitter rival Ian McCulloch, were quickly finding a way to transform post-punk’s anti-macho anxiety into a new kind of arena rock.

By the time the Teardrop Explodes released Wilder in November, their record-collector mix of Beatles and Love-quoting ‘60s psych, discreet funk and military brass sounded like four bookish hippies on magic mushrooms adrift in a nightclub full of narcissistic peacocks on ecstasy. Wilder bombed spectacularly and The Teardrops Explodes never made another album.

Of course, Wilder’s commercial failure never made it a bad record. This is its second reissue – the first was in 2000 – and Cope’s long journey from pop eccentric to modern antiquarian and national treasure has only increased the cult cachet of his first magnificent failure of a band. But it’s still some shock to rediscover just how great, brave and strange Wilder sounds now, mercifully free of the desperation to cross over that even post-punk puritans like Scritti Politti and Gang Of Four fell for at the time.

Wilder’s melodies sound timeless and deliciously free of conventional logic. Its rhythms, inspired by the returning David Balfe’s love of David Byrne and Brian Eno, reject straight time for adventures in syncopation and globe-trotting experiment. Its lyrics – packed with in-jokes about the Liverpool scene, Ian McCulloch’s sister, and Cope, McCulloch and Pete Wylie’s legendary six-week band The Crucial Three – are full of dark winks and unlikely connections between Palestinian freedom fighters and characters from David Copperfield… and that’s just within the prowling, spooked “Like Leila Khaled Said”.

“Bent Out Of Shape”, “Passionate Friend” and “Colours Fly Away” are flawed but fabulous attempts to cemulate “Reward”. “Tiny Children” and “The Great Dominions” are the show-stopping ballads, Cope at his man-child best on the latter, somehow making the “Mummy, I’ve been fighting again” refrain poignant rather than pathetic, as Balfe’s Prophet 5 synth percussion throbs ominously beneath him.

Conflict and breakdown are the album’s themes, as Cope’s band, drug-addled brain and first marriage were collapsing simultaneously. But Cope is quintessentially English, so the mood is stoic, playful, self-mocking.

In poptastic 1981, Wilder made little sense. In 2013, where the musical landscape is full of well-read Dirty Projectors and Wild Beasts and Vampire Weekends, artily fusing psychedelic mindsets and world music motifs, the Teardrop Explodes’ final album sounds entirely contemporary and reveals itself as way ahead of its time. But the clincher is its embrace of the sadness of ending things, and our knowledge that Cope would leave Liverpool and The Teardrop Explodes far behind and go on to bigger adventures. “I could make a meal/Of this wonderful despair I feel”, Cope croons, soft and throaty, on “Tiny Children”. Wilder does exactly that, and then swallows, belches and looks to the future.

Extras: Excellent second disc comprising B-sides, the final, posthumous “You Disappear From View” EP (most of which also appeared on the 2000 reissue), and BBC sessions. Plus revealing, self-deprecating sleevenotes from Messrs Tate, Balfe and Cope.

7/10

Garry Mulholland

Q&A

David Balfe

Were the Wilder sessions as acid-fried as legend insists?

No! Acid was hovering in the background and influencing a certain adventurousness. But you can’t live your life on it.

In your sleevenotes for the reissue you state that Wilder isn’t as good as debut album Kilimanjaro. Why?

We were trying to fuck about with things and throw funk in with trumpets and cinematic concepts of music, and I don’t know whether we pulled it off. I went on to spend the next twenty years being an A&R man (Balfe mentored Blur and was the subject of “Country House”) and I look at a song like “Bent Out Of Shape” in terms of adding this and taking away that and it could’ve been a big hit single.

Is it true that you locked Julian Cope and Gary Dwyer out of the sessions for the third album? Or that Dwyer chased you through the grounds of Rockfield Studios with a loaded shotgun?

No. One of the things Julian does – which I admire enormously – is mythologise everything.

Julian has always been adamant that The Teardrop Explodes will never reform. Is this a good thing?

I think he’s totally right. The part of me that would love to get onstage and play those songs with me old mates would quite like to do it. But I do admire Julian’s integrity.

.