In 1967, Tim Buckley’s star was in the ascendant. Performing off the back of a promising debut album, released the previous year, Buckley was playing clubs in the Village, as part of the folk firmament; supports for groups like The Doors, Jefferson Airplane and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and fes...

In 1967, Tim Buckley’s star was in the ascendant. Performing off the back of a promising debut album, released the previous year, Buckley was playing clubs in the Village, as part of the folk firmament; supports for groups like The Doors, Jefferson Airplane and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and festivals like Bread For Heads at the Village Theater. He seemed oddly positioned – notionally connected to a folk scene, even Tim Buckley’s period-piece production couldn’t hide an artist whose ambitions far outstripped both the genre’s conventions and the music industry’s machinations. And while he was dissatisfied with that debut – Buckley has said, “going into the studio was like Disneyland, I’d do anything anybody said” – on “Song Of The Magician” and “Song Slowly Song”, a striking voice made the most of its context.

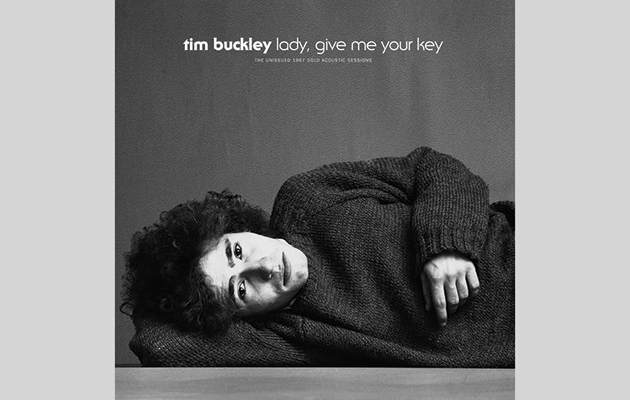

1967’s follow-up, Goodbye & Hello, still reads as Buckley’s coming out party: it’s confident and quietly experimental. Before that album was recorded, though, Jac Holzman, who’d signed Buckley to Elektra, was asking for the seemingly impossible, insisting that this unpredictable singer-songwriter, and his poet collaborator and friend Larry Beckett, write some pop songs for 7” singles. The first half of Lady, Give Me Your Key, a release that has come about largely thanks to curator Pat Thomas, begins by documenting the results.

It’s not exactly promising. Beckett and Buckley may have sneered a little at Holzman’s demand that they work toward pop, but both “Sixface” and “Contact” suggest Elektra would have their work cut out for them anyway, subversive intent or not. “Contact” is particularly clumsy, its leaps in time signature writing an awkward gait into the song’s flow. “Sixface” is marginally more successful, its evocation of seeing the “little girl/Spin it around”, with Buckley’s soaring “come here woman” lyric unreeling over simple strums on the 12-string, capturing something of pop’s psychedelic phase.

With “Lady, Give Me Your Key” and “Once Upon A Time”, though, these sessions come into their own. Both eventually recorded for an unreleased single, only the latter has surfaced in its re-recorded form, on the Where The Action Is? Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968 boxset. There, it’s an odd, inconclusive curio; here it’s surprisingly effective, though, overshadowed by this collection’s title song, a poised performance heavy with longing, the opening, chiming filigrees on guitar descending around a silvery E-string purr.

Performances like this, denuded as they are, sit neatly between Buckley’s first two albums. They gesture toward the more emotionally complex songs shepherded into being, thanks to Jerry Yester’s sympathetic production, on Goodbye & Hello. On that album, Yester imagines and constructs a tableau for each song, though it’s also clear that Buckley has found his métier in his writing, and greater power in his delivery. Songs like “Hallucinations”, “I Never Asked To Be Your Mountain” and “Goodbye & Hello” all signal ways out of the folk singer cul-de-sac that Buckley occasionally risked, the latter through a strange combination of baroque and surrealism, the former two with their unexpected sideways swerves.

Up until now, though, live albums have been the best way to hear the songs from Goodbye & Hello without Yester’s bells and whistles. Buckley’s live performances were notoriously mercurial things, and you can never be entirely sure quite what you’ll get from Buckley in the live setting, so there’s a particular appeal to hearing him demo these songs: consider them audio Post-It notes, promises of what could be. They also allow us all to hear the intricacy of the relation Buckley built between lyrics and his unique guitar playing.

“Once I Was”, one of Buckley’s great devotionals, is even more mordant and melancholy here: the shift from the stately processional of the verse, and the shape-shifting swoon that Buckley pulls out of his larynx for the chorus – note his vibrato as he sighs ‘will you ever remember me’ – is particularly devastating. “I Never Asked To Be Your Mountain”, by contrast, is almost accusatory in its restrained fury, though even with such investment in the performance, you can hear the subtle touches that Buckley worked into his playing, almost as muscle memory. Listen, for example, to the way the rhythm carves great physicality from the guitar, emphasising down strokes to punctuate the inflections of his vocal delivery. It’s made all the more poignant when you remember the song’s address, in part, of his failed marriage.

Those two songs, and a bleakly compelling run-through of “Pleasant Street”, make up the demo tape included here. The rest of the material is drawn from an acetate found in Yester’s possession, where Buckley sketches potential material for Goodbye & Hello. The modernist madrigal “Knight-Errant” borders on the whimsical, were it not for the poetry of Buckley’s chord changes, which shape the song into something unexpected. “Carnival Song” is as playful as it is on Goodbye & Hello, Buckley touching base with the gentle, child-like lyricism that was, at this point, the trademark of The Beatles at their most limpidly psychedelic.

For Buckley aficionados and obsessives, though, the draw of the acetate – as with the demo tape – will be the previously unavailable, or unheard songs. Of the final three unreleased songs, only “I Can’t Leave You Lovin’ Me” has surfaced before, on Live At The Folklore Centre 1967; on that recording, it’s maxed-out and rushing on nervous energy, a drive it shares with the version from the acetate, though here, in the demo stages, the song’s dynamics are more assured, with the wistfulness of the chorus undercut by the propulsion of the guitar.

The real surprise, though, is hearing the lustrous “Marigold”, and then discovering it wasn’t even under consideration for Goodbye & Hello. A gentle, wistful reminiscence, its fragility echoes the less demonstrative moments on that album – with sympathetic production, it could have happily nestled alongside “Morning Glory” and “Knight-Errant”. “She’s Back Again”, in contrast, almost reaches a country-ish lilt, with Buckley scaling his falsetto in mere moments of the song opening: this sounds, to all intents and purposes, as though it could have fallen from demos for The Byrds’ Younger Than Yesterday.

1967 would prove a transformative year for Buckley, though in many ways it’s hard to pick a year that wouldn’t offer some kind of transformation for this questing artist. After the release of Goodbye & Hello, his horizons would open dramatically, and immersion in jazz and other musics had Buckley bobbing in a sea of sound, working toward the open-ended miasma of 1969’s Happy Sad and 1970’s Starsailor. For now, Lady, Give Me Your Key shows us some of the steps Buckley took, during a feverishly creative year, to pursue the totality of music.