Some live albums document a tour. Others are souvenirs of a single, magnetic performance. And then there are others, like a Tim Buckley album issued in 1994 by the LA-based Manifesto label, that seem to chronicle not so much an event as an essence. Connecting us to the voice and vision of a long-...

Some live albums document a tour. Others are souvenirs of a single, magnetic performance. And then there are others, like a Tim Buckley album issued in 1994 by the LA-based Manifesto label, that seem to chronicle not so much an event as an essence. Connecting us to the voice and vision of a long-departed cult hero, Live At The Troubadour 1969 shone a light on two September evenings when Buckley forged new directions in folk-jazz at a West Hollywood nightclub. Receiving some good reviews, the album joined two prior live releases, Peel Sessions and Dream Letter: Live In London 1968, in his posthumous catalogue.

Buckley would have turned 70 this year, a poignant anniversary that evidently prompted Manifesto – run by Evan Cohen, a nephew of Buckley’s former manager Herb – to have another rummage in its archives. Venice Mating Call and Greetings From West Hollywood have been assembled from the same shows as Live At The Troubadour, drawing on five sets that Buckley performed over two nights (four before an audience, one a rehearsal) and repeating none of the versions that made up the 1994 album. Between them, Venice Mating Call and Greetings From West Hollywood add about two hours and 45 minutes of unreleased material to what’s out there.

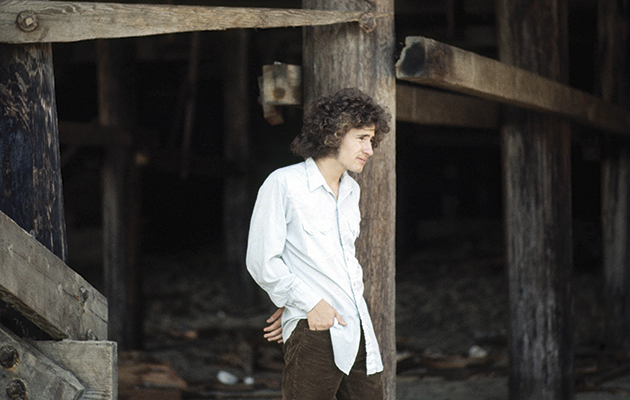

Buckley, just 22 when these gigs took place, was about to make his fourth and final album for Jac Holzman’s Elektra label. Launched as a folk-rocker in 1966, he now viewed himself primarily as a jazz singer, which may be one reason why these albums often occupy a similar meditative headspace to Astral Weeks; rather than racing to the point, Buckley turns single words and individual syllables into lingering, probing ecstasies. Indeed, he’s transported within seconds of strumming his first chord on “Buzzin’ Fly”, the opening song on both albums, and immediately can be heard humming to himself, squealing, yelping, moaning sensually and – on Venice Mating Call – happily whistling.

The albums take somewhat different routes, offering alternative views of roughly the same setlist, before they really start to cook around track five or six. Venice Mating Call, a two-disc set, achieves take-off on “Gypsy Woman”, from Buckley’s then-current album Happy Sad. Lee Underwood, his lead guitarist, switches to electric piano and a groove starts up. Rolling and pulsing like Bitches Brew, it withdraws into a long percussion-only section, whereupon another groove gets going and Underwood returns to his guitar. Throughout all the changes, a delirious Buckley seems hellbent on locating every note in his four-octave range in whichever order he sees fit. It’s an astounding feat of singing. Really, the producers of The Voice should send an MP3 of “Gypsy Woman” to every applicant and tell them to try again in 10 years.

A similar epiphany, meanwhile, occurs in “Nobody Walkin’” on Greetings From West Hollywood. After a discouraging start (“Sounds horrible,” Buckley mutters), it soon livens up (“Yeah! All night long!”) and – again – Buckley rhapsodises and free-associates while his band play a Bitches Brew electric piano groove for a head-nodding 12 minutes. This is some pretty advanced stuff for the Troubadour crowd. Miles Davis had recorded Bitches Brew in New York only a fortnight earlier, and nobody outside Columbia Records would hear any of it until the following March.

Not every song on these sets will send people scurrying to check the recording dates of groundbreaking jazz-rock records. A lot of Buckley’s music is easy to lie back and luxuriate in. No Mingus or Dolphy expertise is needed to appreciate the sweet, swoony words and serene tempo of “Blue Melody”, for instance. But it’s telling that, with Happy Sad not even two months old, Buckley was already previewing the next album he would make (Lorca) and the one after that (Blue Afternoon), while pointedly ignoring the one that had won him his plaudits in the first place (Goodbye And Hello).

Spread across the second disc of Venice Mating Call are the five songs from Lorca – a formidable, fanbase-polarising step into the unknown that even the avowedly pro-artist Holzman found hard to swallow. Its title track, not yet saturated in that eerie pipe organ, is performed on a marimba and lacks the scary drama of the studio version.

Other tracks, however, are fully formed. Literally so in the case of “Driftin’”, which, give or take a bit of EQing, is revealed to be the same eight minutes of music that appears on Lorca’s second side. It gets a great reception, too. How ironic to hear Buckley’s fans in 1969 warmly applauding an album that would alienate so many of them when it came out in 1970.

Attractively presented and well recorded, Venice Mating Call and Greetings From West Hollywood will be lapped up by Buckley completists and should appeal to casual fans of Happy Sad and Blue Afternoon. Issuing this music as two separate 1CD and 2CD packages does seem an unnecessarily pedantic way of making it available, though, especially as the sets duplicate two songs (“Blue Melody” and “Chase The Blues Away”) and share identical sleevenotes. Wouldn’t an all-embracing 3CD release have been a more sensible idea? But then, if everything in the world made sense, Tim Buckley would still be alive.