As inquisitive music fans seek out ever more interesting textures and beats from around the world, it comes as no surprise to see an exotic Touareg blues outfit from the deserts of Mali being championed by such highbrow rock royalty as Brian Eno, Thom Yorke, Robert Plant, Bono, Chris Martin and TV On The Radio. However, when The Sun, The Mirror and dear old Preston from The Ordinary Boys start enthusiastically raving about them, you realise that the tipping point has arrived. Tinariwen have officially become Rather Popular. And the Touareg/rock’n’roll love-in is fully reciprocated. Tinwariwen’s founding father and frontman, Ibrahim “Abaraybone” Ag Alhabib, was always as much a fan of Santana, Bob Marley and Led Zeppelin as he was of Touareg folk melodies. His co-leader Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni grew up listening to tapes by Willie Nelson, The Bee Gees and Boney M (“in the desert, you listen to whatever you can get your hands on,” he explains), while younger bandmembers are happy to race around the desert in 4x4s playing Motörhead and Metallica. They’ve been going, in various forms, since the early 1980s, releasing their first album proper in 2001, but things have really taken off since signing to the rock label Independiente in 2007. They’ve since played at Glastonbury, Coachella and Roskilde; they’ve been joined on stage by Robert Plant, Carlos Santana and Taj Mahal; late last year they played a series of uneasy collaborations with English folktronica act Tunng in an eccentrically programmed UK tour. Of course, it helped that the backstory – Ibrahim’s father was killed by the Malian military for helping Touareg rebels, and Ibrahim and other members later trained in a Libyan guerrilla camp, making music to mourn their dead comrades – was sufficiently hardcore that it made Tupac Shakur look like Little Lord Fauntleroy. In a culture obsessed with “keeping it real” it added a wild man authenticity to their twisted, spartan take on the blues. Although Tinariwen might have been less convincing had they come from Ruislip, it’s important not to let the remarkable biography overshadow the music. A cat’s cradle of wiry funk guitar riffs played over ragged, galloping hand drums, topped by growling, ululating vocals, it seemed to reunite pre-war Delta Blues with its distant African cousins. There were traces of Mali’s hypnotic jeli griots and kora players; there were folk melodies that came from the dislocated, lonesome, nomadic Touareg desert culture from which the band emerged, but when added together it invoked odd but curiously apposite comparisons: Can, Captain Beefheart, The Clash, Black Sabbath. Their last album, 2007’s Water Is Life album, produced in a Bamako studio by Robert Plant’s guitarist Justin Adams, was superficially raw but subtly arranged. The traditional hand drums were multi-tracked and beefed up with handclaps, while the guitars were occasionally treated with wah-wah pedals, fuzzboxes and touches of studio technology. Imidiwan: Companions strips away such modern accoutrements and sees engineer Jean-Paul Romann recording them in situ in a series of remote Malian villages, his portable studio powered by a chugging generator. Everything sounds deliciously grubby and unpolished – the kora-style patterns on “Lulla” seem to tumble out of the guitars in a gloriously haphazard manner; the jittery “Enseqi Ehad Didagh (Lying Down Tonight)”, negotiates the wonderfully disorientating time-signature of 9/16 with a ramshackle charm. Oddly, the more raw and lo-fi you record Tinariwen, the more the cross-cultural connections start to jump out. “Tenhert (The Doe)” is based around a killer blues riff that recalls Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning”, all the time accompanied by half-spoken, arrhythmic rapping. “Kel Tamashek (The Tamashek People)”, based around a discordant acoustic guitar drone, starts off like an Incredible String Band miniature before a thumping bass drum figure recalls Animal Collective. Most of the songs are based around single-chord riffs, but added textures come from the female back-up vocalists – singing, slightly chaotically, in unison, like a Tuareg Bananarama, they add a gleefully poppy sheen to the anthemic “Imidiwan Afrik Tendam (My Friends From All Over Africa)” or the lazy funk of “Tahult In (My Salvation)”. The slow-burning waltz “Tamodjerazt Assis (Regret Is Like A Storm)” is the only track featuring Tuareg poet and occasional bandmember Japonais (“he represents the true soul of Tinariwen,” says Ibrahim, “uncompromising and untameable, which is why he is not very good on tour…”). The album ends with a hidden track “Ere Tesfata Adounia” – an Eno-esque series of spooky, barely stroked guitar effects, feeding back through the speakers, as haunting as a desert wind. It serves as a membrane linking ancient Africa with 21st century electronica – the ghost in the machine of rock’n’roll. JOHN LEWIS For more album reviews, click here for the UNCUT music archive

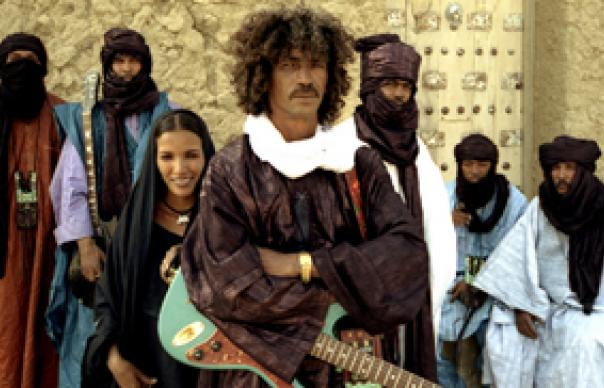

As inquisitive music fans seek out ever more interesting textures and beats from around the world, it comes as no surprise to see an exotic Touareg blues outfit from the deserts of Mali being championed by such highbrow rock royalty as Brian Eno, Thom Yorke, Robert Plant, Bono, Chris Martin and TV On The Radio. However, when The Sun, The Mirror and dear old Preston from The Ordinary Boys start enthusiastically raving about them, you realise that the tipping point has arrived. Tinariwen have officially become Rather Popular.

And the Touareg/rock’n’roll love-in is fully reciprocated. Tinwariwen’s founding father and frontman, Ibrahim “Abaraybone” Ag Alhabib, was always as much a fan of Santana, Bob Marley and Led Zeppelin as he was of Touareg folk melodies. His co-leader Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni grew up listening to tapes by Willie Nelson, The Bee Gees and Boney M (“in the desert, you listen to whatever you can get your hands on,” he explains), while younger bandmembers are happy to race around the desert in 4x4s playing Motörhead and Metallica.

They’ve been going, in various forms, since the early 1980s, releasing their first album proper in 2001, but things have really taken off since signing to the rock label Independiente in 2007. They’ve since played at Glastonbury, Coachella and Roskilde; they’ve been joined on stage by Robert Plant, Carlos Santana and Taj Mahal; late last year they played a series of uneasy collaborations with English folktronica act Tunng in an eccentrically programmed UK tour.

Of course, it helped that the backstory – Ibrahim’s father was killed by the Malian military for helping Touareg rebels, and Ibrahim and other members later trained in a Libyan guerrilla camp, making music to mourn their dead comrades – was sufficiently hardcore that it made Tupac Shakur look like Little Lord Fauntleroy. In a culture obsessed with “keeping it real” it added a wild man authenticity to their twisted, spartan take on the blues.

Although Tinariwen might have been less convincing had they come from Ruislip, it’s important not to let the remarkable biography overshadow the music. A cat’s cradle of wiry funk guitar riffs played over ragged, galloping hand drums, topped by growling, ululating vocals, it seemed to reunite pre-war Delta Blues with its distant African cousins. There were traces of Mali’s hypnotic jeli griots and kora players; there were folk melodies that came from the dislocated, lonesome, nomadic Touareg desert culture from which the band emerged, but when added together it invoked odd but curiously apposite comparisons: Can, Captain Beefheart, The Clash, Black Sabbath.

Their last album, 2007’s Water Is Life album, produced in a Bamako studio by Robert Plant’s guitarist Justin Adams, was superficially raw but subtly arranged. The traditional hand drums were multi-tracked and beefed up with handclaps, while the guitars were occasionally treated with wah-wah pedals, fuzzboxes and touches of studio technology. Imidiwan: Companions strips away such modern accoutrements and sees engineer Jean-Paul Romann recording them in situ in a series of remote Malian villages, his portable studio powered by a chugging generator. Everything sounds deliciously grubby and unpolished – the kora-style patterns on “Lulla” seem to tumble out of the guitars in a gloriously haphazard manner; the jittery “Enseqi Ehad Didagh (Lying Down Tonight)”, negotiates the wonderfully disorientating time-signature of 9/16 with a ramshackle charm.

Oddly, the more raw and lo-fi you record Tinariwen, the more the cross-cultural connections start to jump out. “Tenhert (The Doe)” is based around a killer blues riff that recalls Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning”, all the time accompanied by half-spoken, arrhythmic rapping. “Kel Tamashek (The Tamashek People)”, based around a discordant acoustic guitar drone, starts off like an Incredible String Band miniature before a thumping bass drum figure recalls Animal Collective.

Most of the songs are based around single-chord riffs, but added textures come from the female back-up vocalists – singing, slightly chaotically, in unison, like a Tuareg Bananarama, they add a gleefully poppy sheen to the anthemic “Imidiwan Afrik Tendam (My Friends From All Over Africa)”

or the lazy funk of “Tahult In (My Salvation)”.

The slow-burning waltz “Tamodjerazt Assis (Regret Is Like A Storm)” is the only track featuring Tuareg poet and occasional bandmember Japonais (“he represents the true soul of Tinariwen,” says Ibrahim, “uncompromising and untameable, which is why he is not very good on tour…”).

The album ends with a hidden track “Ere Tesfata Adounia” – an Eno-esque series of spooky, barely stroked guitar effects, feeding back through the speakers, as haunting as a desert wind. It serves as a membrane linking ancient Africa with 21st century electronica – the ghost in the machine of rock’n’roll.

JOHN LEWIS

For more album reviews, click here for the UNCUT music archive