Tom Waits has long been the leading ambassador for the American bohemian tradition, a role he inherited from the beats, bums and folkies of the '60s. And with this three-disc, 54-track set, he really is spoiling us. Culled in roughly equal proportions from previously recorded "orphan" tracks heretofore lacking a secure home in his oeuvre, and brand new material, the collection is divided into separate anthologies of Bawlers, Brawlers and Bastards, roughly correspondent respectively with ballads, blues, and bizarro items that don't sit comfortably in any category. It’s remarkable, though, how much of a piece the entire set is, reflecting how skilfully Waits has welded the various tributary styles of his art into a seamless whole. Whether they involve melancholy piano, wan banjo, gutbucket blues guitar, rumbustious horns, mouth percussion, or the sturm-und-clang of his Harry Partch-inspired homemade instruments, all these tracks are instantly recognisable as Tom Waits. This even holds for the cover versions of such things as The Ramones' "The Return Of Jackie And Judy", Daniel Johnston's "King Kong" or Brecht & Weill's "What Keeps Mankind Alive", all of which instantly adopt his musical character, like animals assuming the protective colouration of their surroundings. They have good reason to need protection, too: the world of Waits' Orphans is a tough and tragic, often brutal place, where the dice invariably roll snake-eyes, and any glimpse of love is but a fleeting memory. Has there ever been a sadder couplet than that which opens "The World Keeps Turning", written for the soundtrack to Pollock: "On our anniversary/There'll be someone else where you used to be"? If there has, it's probably lurking here, in similarly lachrymose laments like "The Fall Of Troy", an account of how a young boy's death impacts upon his family and friends, which opens with the observation, "It's the same with men as with horses and dogs/Nothing wants to die". A similar grim mordancy holds for most of Waits' protagonists - the drifter brought low on "Fannin Street"; the farmer who loses his farm in a flood, only to see his beloved leave town. But even if they're as bereft and abandoned as the hobo who's "Lost At The Bottom Of The World", the tiniest dewdrop can shine a glimmer of redemption into their world: "Well God’s green hair is where I slept last night/He balanced a diamond on a blade of grass". It's perhaps the case, as Waits suggests on the stealthy tango of clarinet and bowed saw "Little Drop Of Poison", that a touch of mischief adds a little spice to life, but it has to be in the right proportion, like the poison in the Fugu fish. Something similar applies to Waits' music, which always has the devil about it, some spark of intrigue that sets it apart from the routine run of singer-songwriter offerings. One's as unlikely to find David Gray, for instance, wielding dramatic metal percussion, wheezing rhythmically like a rusty iron lung, or attempting the weird psychobilly blend of staccato pedal steel and ramshackle horns that accompanies "Lie To Me”. In general, though, the arrangements on the Bawlers songs are subtler and more sensitive, with a wan tone well suited to the material. The mood changes significantly for Brawlers, which comprises mostly raucous, grungy blues, raggedy boogies, whiskery shuffles and barroom stomps delivered in Waits' distinctive rumble'n'clank manner - a delirious, rowdy sound in which can be discerned the godfatherly presences of Howlin' Wolf, Harry Partch and Captain Beefheart. This disc also contains what is undoubtedly Waits' most overtly political song, "Road To Peace", an account of a young suicide bomber's attack on a bus in Jerusalem, and the ghastly spiral of retribution it triggers. A stinging indictment of the fundamentalism afflicting all sides in the conflict, Waits serves his bitterest condemnation for the measly president insulated from his actions thousands of miles away, blithely fulfilling Kissinger's deadly notion that "...We have no friends; America has only interests". All the more devastating, too, for being virtually the only direct protest song in Waits's entire catalogue. There's so much more to enjoy here - the adaptations of Kerouac in "Home I'll Never Be" and "On The Road"; the caterwauling multi-tracked Tom choir bawling out "Goodnight Irene"; the prisoner in "Fish In The Jailhouse" bragging about his ability to pick locks with a fishbone; lines like "Well, the rat always knows when he's in with weasels"; and above all, the overarching humanism that enlightens even the most sombre corners of this massive project. It’s an attitude perhaps best encapsulated in "Bend Down The Branches", an allegorical observation about how trees (ie humans) may get old, but never ugly: "You're like a willow, once you were gold/We're made for bending, even beauty gets old". There's plenty that's old and beautiful about these Orphans. By Andy Gill

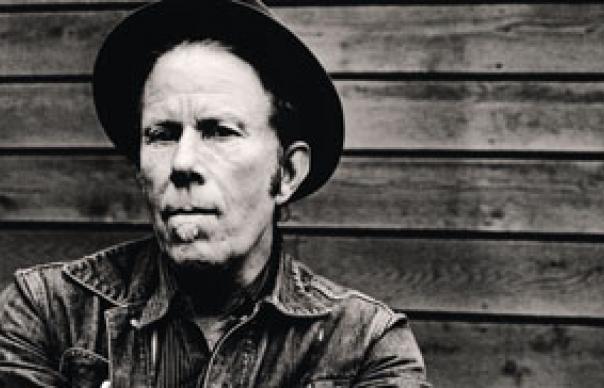

Tom Waits has long been the leading ambassador for the American bohemian tradition, a role he inherited from the beats, bums and folkies of the ’60s. And with this three-disc, 54-track set, he really is spoiling us.

Culled in roughly equal proportions from previously recorded “orphan” tracks heretofore lacking a secure home in his oeuvre, and brand new material, the collection is divided into separate anthologies of Bawlers, Brawlers and Bastards, roughly correspondent respectively with ballads, blues, and bizarro items that don’t sit comfortably in any category.

It’s remarkable, though, how much of a piece the entire set is, reflecting how skilfully Waits has welded the various tributary styles of his art into a seamless whole. Whether they involve melancholy piano, wan banjo, gutbucket blues guitar, rumbustious horns, mouth percussion, or the sturm-und-clang of his Harry Partch-inspired homemade instruments, all these tracks are instantly recognisable as Tom Waits. This even holds for the cover versions of such things as The Ramones’ “The Return Of Jackie And Judy”, Daniel Johnston’s “King Kong” or Brecht & Weill’s “What Keeps Mankind Alive”, all of which instantly adopt his musical character, like animals assuming the protective colouration of their surroundings.

They have good reason to need protection, too: the world of Waits’ Orphans is a tough and tragic, often brutal place, where the dice invariably roll snake-eyes, and any glimpse of love is but a fleeting memory. Has there ever been a sadder couplet than that which opens “The World Keeps Turning”, written for the soundtrack to Pollock: “On our anniversary/There’ll be someone else where you used to be”?

If there has, it’s probably lurking here, in similarly lachrymose laments like “The Fall Of Troy”, an account of how a young boy’s death impacts upon his family and friends, which opens with the observation, “It’s the same with men as with horses and dogs/Nothing wants to die”. A similar grim mordancy holds for most of Waits’ protagonists – the drifter brought low on “Fannin Street”; the farmer who loses his farm in a flood, only to see his beloved leave town. But even if they’re as bereft and abandoned as the hobo who’s “Lost At The Bottom Of The World”, the tiniest dewdrop can shine a glimmer of redemption into their world: “Well God’s green hair is where I slept last night/He balanced a diamond on a blade of grass”. It’s perhaps the case, as Waits suggests on the stealthy tango of clarinet and bowed saw “Little Drop Of Poison”, that a touch of mischief adds a little spice to life, but it has to be in the right proportion, like the poison in the Fugu fish.

Something similar applies to Waits’ music, which always has the devil about it, some spark of intrigue that sets it apart from the routine run of singer-songwriter offerings. One’s as unlikely to find David Gray, for instance, wielding dramatic metal percussion, wheezing rhythmically like a rusty iron lung, or attempting the weird psychobilly blend of staccato pedal steel and ramshackle horns that accompanies “Lie To Me”. In general, though, the arrangements on the Bawlers songs are subtler and more sensitive, with a wan tone well suited to the material.

The mood changes significantly for Brawlers, which comprises mostly raucous, grungy blues, raggedy boogies, whiskery shuffles and barroom stomps delivered in Waits’ distinctive rumble’n’clank manner – a delirious, rowdy sound in which can be discerned the godfatherly presences of Howlin’ Wolf, Harry Partch and Captain Beefheart.

This disc also contains what is undoubtedly Waits’ most overtly political song, “Road To Peace”, an account of a young suicide bomber’s attack on a bus in Jerusalem, and the ghastly spiral of retribution it triggers. A stinging indictment of the fundamentalism afflicting all sides in the conflict, Waits serves his bitterest condemnation for the measly president insulated from his actions thousands of miles away, blithely fulfilling Kissinger’s deadly notion that “…We have no friends; America has only interests”. All the more devastating, too, for being virtually the only direct protest song in Waits’s entire catalogue.

There’s so much more to enjoy here – the adaptations of Kerouac in “Home I’ll Never Be” and “On The Road”; the caterwauling multi-tracked Tom choir bawling out “Goodnight Irene”; the prisoner in “Fish In The Jailhouse” bragging about his ability to pick locks with a fishbone; lines like “Well, the rat always knows when he’s in with weasels”; and above all, the overarching humanism that enlightens even the most sombre corners of this massive project. It’s an attitude perhaps best encapsulated in “Bend Down The Branches”, an allegorical observation about how trees (ie humans) may get old, but never ugly: “You’re like a willow, once you were gold/We’re made for bending, even beauty gets old”. There’s plenty that’s old and beautiful about these Orphans.

By Andy Gill