In 1970, Sidiki Diabaté and Djelimady Sissoko recorded an album of instrumental kora duets called Cordes Anciennes (Ancient Strings). Although it was only released in France and Germany on a specialist ethno-musicological label, as western interest grew in ‘world music’, it came to be regarded as a landmark release – not least because it was the first ever recording devoted solely to the rippling, harp-like textures of the kora.

In 1970, Sidiki Diabaté and Djelimady Sissoko recorded an album of instrumental kora duets called Cordes Anciennes (Ancient Strings). Although it was only released in France and Germany on a specialist ethno-musicological label, as western interest grew in ‘world music’, it came to be regarded as a landmark release – not least because it was the first ever recording devoted solely to the rippling, harp-like textures of the kora.

DAVID BOWIE IS ON THE COVER OF THE LATEST UNCUT – ORDER YOUR COPY HERE

More than a quarter of a century later, Lucy Duran, professor of music at the London School of Oriental and African Studies, persuaded Joe Boyd to commission a belated sequel for release on his Hannibal label.

As Djelimady had died in 1981, Duran proposed that Sidiki Diabaté should instead duet with his son Toumani, whose debut album Kaira she had produced in 1988, and who was fast emerging as the most gifted among a new generation of kora players. However, before Duran and her sound engineer Nick Parker reached the Malian capital Bamako in 1997, Sidiki died from a stroke while visiting relatives in Gambia.

Reluctant to abandon the project which she had already decided should be called New Ancient Strings, Duran searched for a new script – and instead of an album of father-and-son duets, decided to record the two sons of the musicians who had made Cordes Anciennes.

At the time, Djelimady’s son Ballaké Sissoko was relatively unknown and New Ancient Strings would be his first appearance on record; but Duran had no doubt that it would work. In jeli tradition the culture is handed down the generations and on Djelimady’s death Ballaké, then only 14, had taken his father’s place in the Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali. What’s more he and Toumani had an intuitive rapport. They were cousins and had grown up side-by-side – Mali’s first president Modibo Keita had given their fathers a plot of land which they divided equally to live together as neighbours.

A week spent scouting for a recording location was fruitless, none of the studios in Bamako proving suitable for the kind of natural, acoustic sound Duran was after. Finally, someone suggested the newly built Palais de Congrès, where they found a vestibule with marble walls and floor which created a perfect, natural reverb. The only problem was that the venue was in constant use throughout the day and early evening and so the space was only available after 10pm – and only for one night.

Yet these obstacles turned out to be to advantages in disguise. The symmetry of the two sons following in their fathers’ footsteps may have been unplanned but it was irresistible. In addition, by the time Toumani and Ballaké came to record New Ancient Strings the calendar had serendipitously clicked round to September 22, the anniversary of the ending of French colonial rule. What better date to record an album paying homage to the country’s most profound musical traditions than Mali’s National Independence Day?

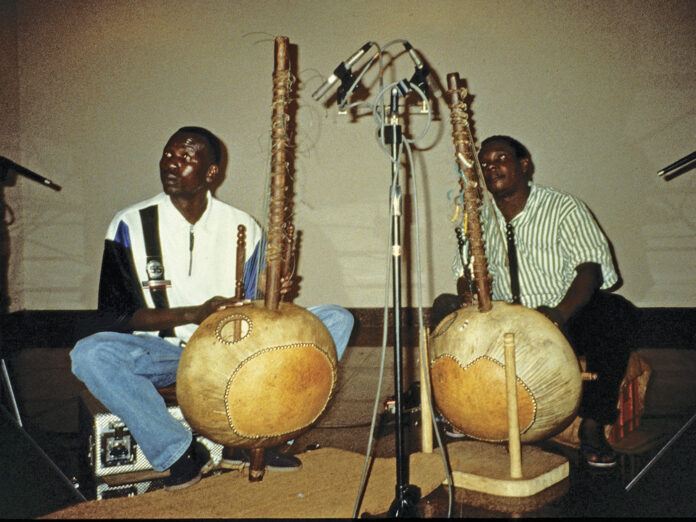

After an hour or more spent chasing out the chirping crickets, it was midnight before tranquility was achieved and recording could begin. Toumani and Ballaké played through the night, entirely live, without second takes, improvising around tunes from the classical Mande repertoire. By seven the next morning, the album was done. Duran subsequently admitted it was the “least produced” album in which she has ever been involved.

If you listen closely in the places where the two kora virtuosi are sparring with each other, you can make a reasonable guess as to who is playing what. Broadly speaking, Sissoko’s playing is perhaps more rhythmic and Diabeté’s more melodically nuanced. But that distinction is too simplistic and, for the most part, the combined 42 strings of the two koras flow together with such perfect contrapuntal calibration between timeless groove and gossamer lyricism that it sounds like a single player with four hands.

If the album can be seen as a tribute to their respective fathers, there are also subtle differences, the “ancient strings” of past generations updated with “new” techniques such as percussive dampening of notes, giving New Ancient Strings a more dynamic sense of light and shade than the album from which it derived its inspiration.

It’s almost impossible to pick out highlights among the eight tracks, which deserve to be listened to as a seamless suite. That said, “Bi Lamban” is a dazzling reworking of a melody alleged to be 800 years old, the minor-key harmonics of “Salaman” ooze with a heart-rending pathos, “Bafoulabe” is as elegant and graceful as anything by Bach or Handel and the lightly pirouetting rhythms of “Cheikhna Demba” are so captivating that Mali’s national television station borrowed the track as its signature tune.

On its release, New Ancient Strings did for the kora what Ravi Shankar did for the sitar in the 1960s, bringing the instrument into the global stream and inspiring western musicians from Björk to Damon Albarn to incorporate its unique sound into their recordings. It’s long been out of print, so if you missed it back then, this long overdue reissue is the perfect way to get acquainted with this vital, timeless, glorious album.