In 1971, with every studio looking for the next Easy Rider, Esquire got so excited about Two-Lane Blacktop that it printed the screenplay and declared it the "movie of the year", without seeing a frame. It's easy to see why they might have come to that conclusion. The film stars James Taylor, then at the height of his success (and dating Joni Mitchell); and Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, the epitome of Californian cool. The director, Monte Hellmann, was a protŽgŽ of "quickie" director Roger Corman, who had worked as an editor on The Wild Angels, and directed Jack Nicholson in two westerns, The Shooting and Ride In The Whirlwind. The story fits in with the counter culture - being the tale of two drifters in a custom '55 Chevy, who challenge Warren Oates - "Korean war vet, an overgrown, maniacal fraternity boy, looking for action" in his yellow Pontiac GTO - to a race across country, with the winner taking the keys to the other's car. Along the way, Taylor ("the Driver") and Wilson ("the Mechanic") pick up "the Girl" (the boyish Laurie Bird), and glide through the disappearing landscapes of Route 66; all rural gas stations and empty diners. But Two-Lane Blacktop flopped, condemning Hellmann to a career as a "gun-for-hire". Occasionally, both director and film would threaten to emerge from the shadows. Hellman was asked to direct Reservoir Dogs, but took an executive role after Tarantino realised he could make it himself. And when Richard Linklater coordinated a Hellman retrospective at Austin's SXSW in 2000, he listed 16 reasons why Two-Lane Blacktop was an American classic. Roughly, these are: it's like a western, and the drivers are old-time gunfighters; because it's like a drive-in movie directed by a French New Wave director; and because, unlike most counter-culture efforts, it isn't about the alienation of the drug culture, it's about the alienation of everybody else, "like Robert Frank's America come alive." It's a far better film than Easy Rider. The screenplay, by Gunsmoke writer Will Corry, and given an existential sheen by Rudy Wurlitzer (who later wrote Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid) is beyond sparse. The Driver, the Mechanic and the Girl barely talk. The few lines they have are delivered flatly, because Hellmann insisted on the actors doing multiple takes after making the journey across state lines. They look exhausted because they are. Oates, meanwhile, grows increasingly crazed, "pickin' up one fantasy after another" on the road, and telling different stories to them all. His passengers bring reminders of death. "If I'm not grounded pretty soon," he tells the sleeping Girl, "I'm gonna go into orbit." From a roadside waitress, he orders: "Champagne, caviar, chicken sandwiches under glass." This, remember, is a man who keeps a bar in the trunk of the GTO, so that when offered a boiled egg by his rivals, he can reciprocate with a drink: "I've got other items, depending on which way you want to go," he boasts. "Up, down, or sideways." Somewhere along the way, the notion of the race dissolves, and the fact that Hellmann was first hired by Corman after a theatrical production of Waiting For Godot starts to make sense. The reason for Two-Lane Blacktop's initial failure is also the reason it endures: it captures the death of 1960s idealism, and shows how it hardly even reached the roadsides of middle-America. It journeys beyond cool, into nihilism. "Everything is going too fast and not fast enough," Oates moans, in the middle of nowhere, reaching for an Alka Seltzer. EXTRAS: Director's commentary - 2* ALASTAIR McKAY

In 1971, with every studio looking for the next Easy Rider, Esquire got so excited about Two-Lane Blacktop that it printed the screenplay and declared it the “movie of the year”, without seeing a frame.

It’s easy to see why they might have come to that conclusion. The film stars James Taylor, then at the height of his success (and dating Joni Mitchell); and Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, the epitome of Californian cool.

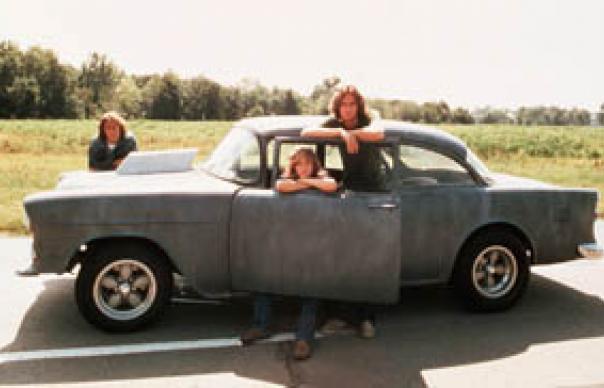

The director, Monte Hellmann, was a protŽgŽ of “quickie” director Roger Corman, who had worked as an editor on The Wild Angels, and directed Jack Nicholson in two westerns, The Shooting and Ride In The Whirlwind. The story fits in with the counter culture – being the tale of two drifters in a custom ’55 Chevy, who challenge Warren Oates – “Korean war vet, an overgrown, maniacal fraternity boy, looking for action” in his yellow Pontiac GTO – to a race across country, with the winner taking the keys to the other’s car. Along the way, Taylor (“the Driver”) and Wilson (“the Mechanic”) pick up “the Girl” (the boyish Laurie Bird), and glide through the disappearing landscapes of Route 66; all rural gas stations and empty diners.

But Two-Lane Blacktop flopped, condemning Hellmann to a career as a “gun-for-hire”. Occasionally, both director and film would threaten to emerge from the shadows. Hellman was asked to direct Reservoir Dogs, but took an executive role after Tarantino realised he could make it himself. And when Richard Linklater coordinated a Hellman retrospective at Austin’s SXSW in 2000, he listed 16 reasons why Two-Lane Blacktop was an American classic. Roughly, these are: it’s like a western, and the drivers are old-time gunfighters; because it’s like a drive-in movie directed by a French New Wave director; and because, unlike most counter-culture efforts, it isn’t about the alienation of the drug culture, it’s about the alienation of everybody else, “like Robert Frank’s America come alive.”

It’s a far better film than Easy Rider. The screenplay, by Gunsmoke writer Will Corry, and given an existential sheen by Rudy Wurlitzer (who later wrote Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid) is beyond sparse. The Driver, the Mechanic and the Girl barely talk. The few lines they have are delivered flatly, because Hellmann insisted on the actors doing multiple takes after making the journey across state lines. They look exhausted because they are.

Oates, meanwhile, grows increasingly crazed, “pickin’ up one fantasy after another” on the road, and telling different stories to them all. His passengers bring reminders of death. “If I’m not grounded pretty soon,” he tells the sleeping Girl, “I’m gonna go into orbit.” From a roadside waitress, he orders: “Champagne, caviar, chicken sandwiches under glass.” This, remember, is a man who keeps a bar in the trunk of the GTO, so that when offered a boiled egg by his rivals, he can reciprocate with a drink: “I’ve got other items, depending on which way you want to go,” he boasts. “Up, down, or sideways.”

Somewhere along the way, the notion of the race dissolves, and the fact that Hellmann was first hired by Corman after a theatrical production of Waiting For Godot starts to make sense. The reason for Two-Lane Blacktop’s initial failure is also the reason it endures: it captures the death of 1960s idealism, and shows how it hardly even reached the roadsides of middle-America. It journeys beyond cool, into nihilism. “Everything is going too fast and not fast enough,” Oates moans, in the middle of nowhere, reaching for an Alka Seltzer.

EXTRAS: Director’s commentary – 2*

ALASTAIR McKAY