The origin of rock’n’roll is partly a matter of nomenclature, and partly of geography. Where does R’n’B end, and rock’n’roll begin? Back in the mid-’50s, there was no decisive border between genres, no line drawn in the sand, but rather a more diffuse boundary, re-drawn with each succe...

The origin of rock’n’roll is partly a matter of nomenclature, and partly of geography. Where does R’n’B end, and rock’n’roll begin? Back in the mid-’50s, there was no decisive border between genres, no line drawn in the sand, but rather a more diffuse boundary, re-drawn with each successive tide, the seas controlled by corruptible media gatekeepers like Alan Freed and Dick Clark. So one day Bo Diddley, for instance, may have been considered R’n’B, the next rock’n’roll.

The situation is further complicated by the regional nature of that era’s popular music, with each area developing its own strain of R’n’B, a process partly determined by the wattage of the local radio transmitter. Nowhere was this regionality more evident than in New Orleans, where the peculiar fingerprint of the city’s music – what Jelly Roll Morton called “the Spanish tinge” – was transmuted into the rumba-rock rhythms of piano legend Professor Longhair; while the Mardi Gras Indian chants of the city’s unorthodox gang culture acquired wider exposure through records like Sugar Boy & His Cane Cutters’ “Jock-A-Mo”, James ‘Sugar Boy’ Crawford’s original 1954 recording of what would subsequently become internationally infectious as “Iko Iko”.

But although promoting a rich diversity of musical styles, regionality could downplay the influence and importance of an artist or recording. New Orleans’ most celebrated musical son Fats Domino, for instance, could lay incontrovertible claim to the first rock’n’roll record with his 1949 debut “The Fat Man” (not included here), though for some reason rock’n’roll sages and historians have bestowed that honour upon “Rocket 88” by Jackie Brenston & His Delta Cats, a 1951 track licensed to Chess Records by Sun Studios genius Sam Phillips. So props, then, to the 19-year-old Ike Turner, whose Kings Of Rhythm lurked behind the Delta Cats sobriquet (Brenston was Ike’s sax player), and who made just a princely $20 for the galloping Oldsmobile tribute. Ironically Turner, whose piano intro would be borrowed for Little Richard’s “Good Golly Miss Molly”, always considered the track R’n’B rather than rock’n’roll – and certainly, Brenston’s enjoyably ramshackle follow-up “Juiced” (“let’s drink some juice, get loose ’til the morning”) stays firmly on the R’n’B side of that divide.

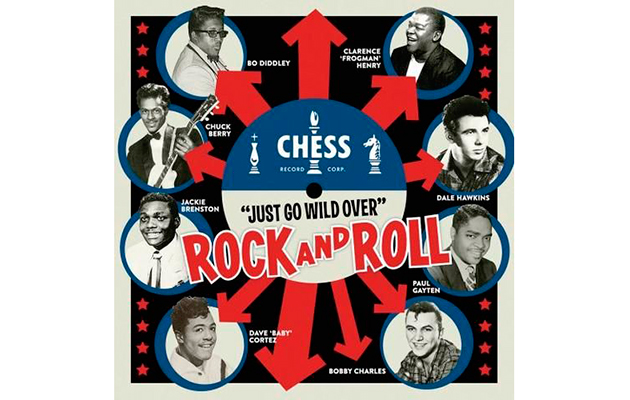

Chess Records, of course, was firmly rooted in R’n’B until April 1955, when Bo Diddley’s eponymous debut single took off, followed in July by Chuck Berry’s motorvating “Maybellene”. This, surely, was the decisive shift to rock’n’roll: both these tracks employed newer, more urgent rhythms than the swing grooves of R’n’B, with more upfront, unashamed sexual energy. The febrile itch of Bo’s guitar and his sidekick Jerome’s shaker on “Bo Diddley” was a dynamic adaptation of the “hambone” style, based on the African “patted juba” form, in which rhythms were patted out by dancers on their own bodies, in lieu of the drums forbidden to slaves. The Diddley-beat remains a hardy virus infecting huge swathes of popular music across the decades, while the equally popular “Who Do You Love” wittily introduced voodoo into rock. “Maybellene”, meanwhile, introduced the world to rock’s first poetic genius, a status confirmed here by a select anthology of fast, witty narrative masterworks – “Johnny B Goode”, “You Never Can Tell” and the peerless “No Particular Place To Go” – and only slightly tainted by the live version of “My Ding-A-Ling” which closes the album.

Around these twin titans scamper a throng of fellow travellers and one-hit-wonders, their variety indicative of the instantly expanding range of the new youth music. Perhaps the most important of these second stringers was Dale Hawkins, whose classic “Suzie Q” oozed predatory sexual threat, both in Dale’s slyly casual vocal and James Burton’s tart, assertive guitar riff. Almost single-handedly, it established swamp-rock as a serviceable sub-genre of its own, ripe for John Fogerty’s imaginative evocations.

A couple of other tracks here are worthy first-string classics. Built around the hook from Mickey & Sylvia’s “Love Is Strange”, Dave ‘Baby’ Cortez’s popular “Rinky Dink” is the kind of organ instrumental that soundtracked fairgrounds and ice rinks (and ITV’s wrestling, grapple fans!) through the ’60s, and proved influential on Booker T & The MG’s, who covered it on their debut album.

Recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studio in New Orleans, Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry’s quirky “I Ain’t Got No Home”, featuring his trademark novelty frog vocal, employed the hard-swinging, propulsive horn sound that Bumps Blackwell perfected there on Little Richard’s early releases. Its engaging charm assured Henry a long and entertaining career, something denied to the creators of less enduring novelties like The Satellites’ corny rocket-age countdown “Blast Off” and the “breathless” gimmick of “Save It” by Mel Robbins, solo pseudonym of Hargus ‘Pig’ Robbins, the legendary blind session pianist featured on Blonde On Blonde.

This was the era when separatist ideas of black and white first began breaking down. Yet another New Orleans legend, Bobby Charles (who wrote “See You Later, Alligator”, among others), is featured here doing a remarkable act of musical blackface with “Time Will Tell”, a loping R’n’B swagger as cool as ice. By contrast, Bobby Sisco’s “Tall Dark And Handsome Man” exemplifies the farmhand rockabilly vocal twang that derived from the other partner in rock’n’roll’s miscegenate marriage of country and blues, a mode that reaches perhaps its furthest extremity with Billy Barrix’s “Cool Off Baby”, whose stammer-stutter delivery dissolves into an incomprehensible stream of staccato vocables. It’s redolent of that scene from In The Heat Of The Night when the hillbilly murderer slips a dime into the diner’s jukebox and stalks stealthily away, aping the lyric of “The Creeper”.

The closest this set gets to that level of sinister charm is probably Eddie Fontaine, whose “Nothin’ Shakin’ (But The Leaves On The Trees)” was a stand-alone classic blending Chuck Berry rhythms with rockabilly snap. Popular with the young George Harrison, it became part of The Beatles’ live repertoire as they built that most impressive of rock’n’roll edifices. Sadly, Fontaine did not fare quite as well, becoming a bit-part actor in TV cop shows, while his own reality began to mirror that of the low-lifes he played. Convictions for grand larceny and child molestation were eventually followed in 1984 by a further conviction for trying to lure another singer into murdering his estranged wife. Sometimes the promise of those rock’n’roll pearls just falls on stony ground, I guess.