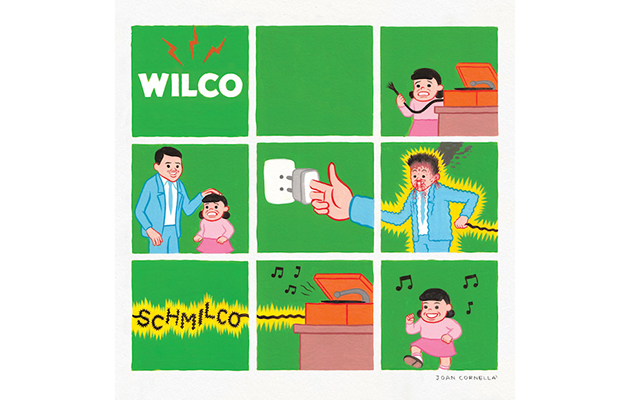

Don’t be fooled by its lighthearted, Nilsson Schmilsson-referencing title – Schmilco is as considered and introspective as the band’s 2015 surprise release Star Wars was spontaneous and exuberant. Stripped back yet unnervingly intense, not unlike Neil Young’s bleak masterpiece On The Beach, Wilco’s tenth studio album is striking for the challenges Jeff Tweedy and his partners have set for themselves as they engage in a tug of war between order and chaos, acceptance and despair.

The folky strummed acoustic on which most of Schmilco’s dozen tracks are built hearkens back to Wilco’s first album, 1994’s A.M.; released at a time when Tweedy was viewed merely as Uncle Tupelo’s second banana, having reacted to Jay Farrar’s abrupt exit by gamely picking up the pieces and making the most of what then seemed like a shot in the dark. Since that modest, engaging and unexpectedly surefooted first step, Farrar’s one-time sidekick and his shifting lineup have accumulated one of the richest, most diverse and ambitious bodies of work of any American band of the last quarter-century. Despite his stature, Tweedy, whose humanity and lack of pretension were at the root of Wilco’s initial appeal, retains his underdog appeal 22 years and 10 albums down the road. The antithesis of a larger-than-life rock star, less enigmatically distant than the similarly adored auteur Thom Yorke, he’s always come off as a friend and confidant, if a troubled one at times, a guy we reflexively root for. Tweedy is unafraid to be unflinchingly honest, but he’s never seemed more vulnerable than he does on this nerve-jangling album.

In the pre-release literature, Tweedy describes the album as “joyously negative… I just had a lot of fun being sour about the things that upset me.” Resourceful as ever, he’s come up with an artfully twisted way to vent his spleen – and more to the point, to expose the depths of his anguish. Time feels suspended within the record’s arid, claustrophobic atmosphere; the running time is less than 37 minutes, only one track breaks four minutes and most are under three, but you can get lost – or trapped – inside it, as in a dream that refuses to release you from its jittery thrall. Tweedy and his cohorts have boiled down each song and instrumental part to its essence – in its starkness, the sound evokes bone and gristle, to the degree that the record’s moments of fleshed-out human warmth are magnified, mirroring the jangled nerves that rattle the frontman’s rumpled, perennially boyish tenor.

In the opening “Normal American Kids”, Tweedy looks back to his youth, but not nostalgically – far from it. The lyric describes feeling apart and unsettled by the existential distance from perceived normalcy, while Nels Cline’s slide wheezes asthmatically, seconding the emotion. “Always hated those normal American kids”, he ruefully concludes. The vibe warms considerably, if temporarily, on the following “If I Ever Was A Child”, with its loping cadence, gilded guitars and textured chorus harmonies, recalling the Byrdsy folk rock of 2007’s lovely Sky Blue Sky. Glenn Kotche’s feverish double-time drumming propels “Cry All Day” while bass player John Stirratt, whose stolid parts counterbalance his bandmates’ extremes, puts his oars in the water to pull against the unchecked energy, suggesting the uneasy duality of agitation and reflectiveness that give the album its distinct character. The band courts anarchy on “Common Sense”, with its fractured stop/start cadence, dissonant guitar chords, queasy slide and what could pass for the zither in “The Third Man Theme” refracted through a bad acid trip. There’s a stretch of spirited acoustic rock’n’roll in the acrimonious “Nope” and the chugging “Something To Lose”, followed by the misanthropic lament “Happiness” (“…depends on who you blame”) and the bonsai short story “Quarters”, before things go haywire again with “Locator”. On this eerie, disjointed track, the underlying mortal dread breaks the surface, as the narrator peers into the abyss, mesmerised, chanting “I hide/Here below”.

Whenever we begin to get comfortable on this record, Tweedy and his cohorts pull the rug out from under us. In the past, they’ve kept us on edge by deftly employing eruptive tonal shifts, the operative modes of Being There and Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, as well as more recent cacophonous disturbances triggered by Cline’s trademark freak-outs like Wilco (The Album)’s “Bull Black Nova” and The Whole Love’s “Art Of Almost”. On Schmilco, by contrast, the approach is sustained and reductive, leading to an emptying out, a detox of the psyche; which is why experiencing the whole of it – culminating with the unsettlingly beautiful “Shrug And Destroy” (the album’s “Norwegian Wood”), the spoken/sung, Velvets-referencing “We Aren’t The World (Safety Girl)” and the blessedly liquid closer “Just Say Goodbye” – ultimately brings such a sense of relief. Without question, Schmilco is Wilco’s quietest, most disquieting album. And if Tweedy’s soul-baring amid these artfully austere backdrops constitutes a performance, it’s a pretty convincing one.