It’s hard to evaluate a miracle using standard critical criteria. Joni Mitchell’s return to the stage at the Newport Folk Festival last July was an event as triumphant as it was wholly unlikely, following her long (and continuing) struggle back to health in the wake of a brain aneurysm in 2015. ...

It’s hard to evaluate a miracle using standard critical criteria. Joni Mitchell’s return to the stage at the Newport Folk Festival last July was an event as triumphant as it was wholly unlikely, following her long (and continuing) struggle back to health in the wake of a brain aneurysm in 2015.

The show preserved and presented here was intended as a public recreation of the Joni Jams, the informal, good-timey, therapeutic evenings of music and laughter which Mitchell has hosted with a bunch of musician friends in recent years. Chief among the Jammers is Brandi Carlile, who was the prime mover and shaker in setting up this event. The Newport concert was billed as Brandi Carlile & Friends, not simply in order to preserve the surprise but because, as fellow Joni Jammers Jess Wolfe & Holly Laessig from Lucius told Uncut last year, nobody was quite sure until the final moments whether Mitchell would do it or not.

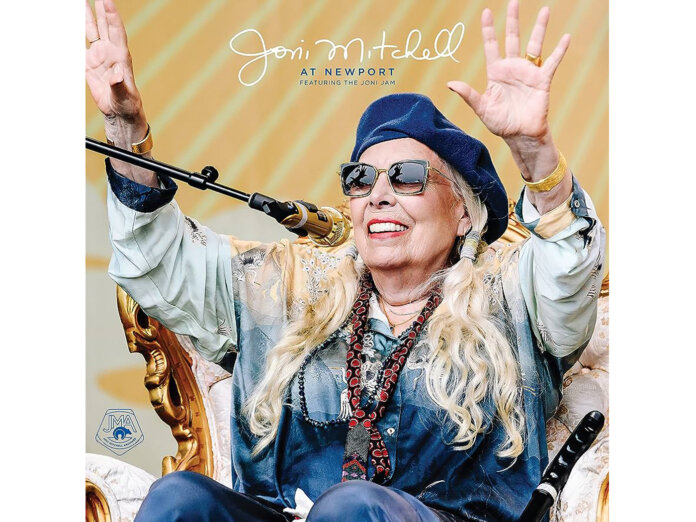

The palpable sense of anticipation and release makes for a stirring opening to the record. Carlile’s warm and teasing introduction – “How are we going to have a Joni Jam without our queen? [Prolonged pause] We’re not!” – unleashes a joyful clamour from the audience, as the dawning realisation sweeps over those lucky souls in attendance that the woman herself is in the building. “Mitchell emerged from the side of the stage, swaying smoothly, in fine summer-style with beret and sunglasses,” writes Cameron Crowe in the liner notes. “Her good-natured mood instantly set the tone.”

Given the extraordinary context, then, normal rules don’t quite apply to this release. Mitchell’s first live performance in two decades, and her first at Newport since 1969, makes for an album that is more historical document than conventional concert recording. It is, variously, an act of love, a therapy session, a reclamation and an honouring. The headline artist is not always audible on all of the 11 tracks, but her presence throughout is indelible.

What we get is a loose ensemble performance, a long way from Mitchell’s intricate solo ruminations of the late ’60s and early 1970s, the jazz-flecked LA Express adventures of the mid-’70s, the later synth-pop years and dusky orchestral manoeuvres. Mitchell slides into the passenger seat alongside a cast of artists which includes Carlile, Marcus Mumford, Dawes’ Taylor Goldsmith, Wynonna Judd, Blake Mills, Allison Russell, Shooter Jennings and Celisse Henderson. Two songs from the full live set have been omitted from the album. There’s no room for the warm-hearted covers of “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” and “Love Potion No 9”, while the running order has been tinkered with, presumably to make the set feel more coherent in album form.

It’s fair to say that Mitchell rarely does the heavy lifting here. Her role onstage is a fluid one: muse-goddess, North Star, shredder, comic foil and sometime singer. There’s no shortage of quality to go around. The playing by her fellow artists is stellar and the backing vocals, in particular, ooze class. Carlile does a particularly nice job as a Joni manqué on a rollicking “Carey”, and although “A Case Of You”, sung as a duet with Mumford, flirts with cocktail schmaltz, Mitchell’s laugh at the end redeems it. “Help Me”, sung by Celisse, is less convincing. Arranged into a ponderous and slightly overwrought plod, it lands a long way from its slinky origins.

Amid all this affectionate sparring, Mitchell moves in and out of focus in sprightly and sometimes unexpected fashion. A spare guitar-and-vocals “Amelia”, sung by Goldsmith and shading into Bill Frisell territory, comes prologued with a chat between Mitchell and Carlile about the road trip which inspired Hejira. There are other scene-stealing cameos: her comical baritone at the end of a breezy “Big Yellow Taxi”; throwing out thrillingly discordant electric guitar lines on an instrumental version of “Just Like This Train”; jumping in with a growled “mean old daddy” at the finale to “Carey”; adding counterpoint to a lilting “Come In From The Cold”, sung winningly by Goldsmith, on which her Canadian accent sounds particularly and poignantly pronounced.

And then, on the relatively rare occasions when Mitchell does deign to take centre stage, she nails it. Performed to piano and low strings, “Both Sides Now” is impossibly touching, several shades deeper still than the moving reinvention she made of the song in the early 2000s. “Something’s lost but something’s gained, in living every day”, she sings in a low, smoky register, still full of nuance and guile, and it feels like a moment of some significance has been marked.

Gershwin’s “Summertime” is simply gorgeous, featuring rolling blues piano, stinging electric guitar lines, and a bravura singing performance which proves beyond doubt that Mitchell’s vocal prowess has merely shifted into new areas rather than diminished. Underlining that point again, she dovetails wonderfully with Carlile on “Shine” and takes control of the closing “The Circle Game”, leading the singalong. When she dissolves into giggles at the end – “So fun!” – you’re reminded of the high-pitched cackle dubbed on to the conclusion of the original recording of “Big Yellow Taxi”. That studio-spliced burst of levity always sounded a little contrived. Now, when Mitchell laughs – and she laughs a lot here – it feels earned, and true.