Subscription Required!

Subscribe to Uncut+ to get access to our special members area where you’ll find every issue of Uncut stretching back to Take 1 in 1997 plus a comprehensive collection of our Ultimate Music Guides and other special editions. Browse issues from our archive in full and use our search engine to hunt down features and reviews in Uncut about your favourite artists

If you are already subscribe to Uncut+ or the print edition of Uncut magazine, simply login below.

Login

Don't have an subscription?

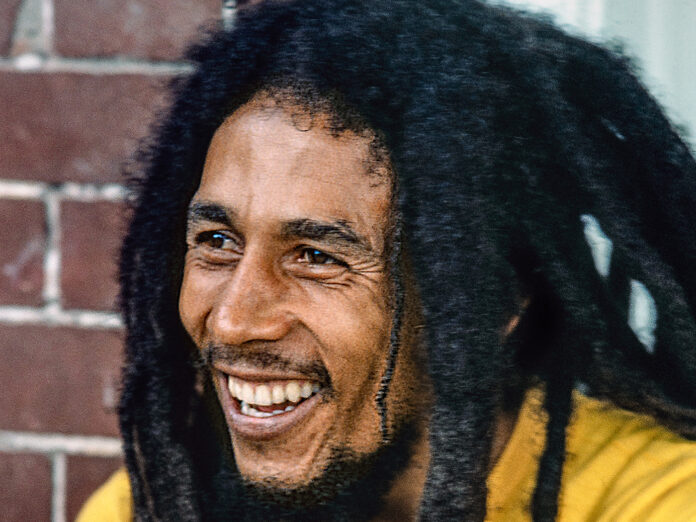

From Uncut’s March 2019 issue [Take 262]. Bob Marley’s bandmates and collaborators chart the musical evolution of a reggae superstar…

“All the albums are great,” proclaims Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett as he casts an eye over The Wailers’ mighty back catalogue. “I played on them all, and I love them all.” Still touring with an incarnation of the band that includes guitarist Donald Kinsey, the original Wailers’ bassist guides Uncut through the records that delivered reggae from the ghettos of Kingston to stadia around the world, making Bob Marley a superstar in the process. Featuring rifts, shootings, spliff-related studio disasters exile, fish curries and ultimately tragedy, with supporting roles for Chris Blackwell and his Island team, as well as latter-day Wailers’ guitarist Junior Marvin, the band’s story is hardly lacking in drama. Through it all, the music developed and deepened.

“With each album, we changed something,” says Family Man, who has lived up to his nickname by fathering 14 children. “I and I were in deep meditation of the works we were doing. We rehearsed, meditated, prepared ourselves every day to record, making sure we never missed a beat.”

THE WAILERS

Catch A Fire

(Island, 1973)

Having recorded with Lee Perry, The Wailers sign to Island and make their international debut, a ground-breaking blend of roots reggae and Western rock textures

ASTON ‘FAMILY MAN’ BARRETT [BASS]: We’d been working with Lee Perry at Randy’s Studio, 17 North Parade, Kingston. It was a wonderful vibe, nice, no complaints. Bob and Lee got along great, until we moved to the next stage! The first time I met Chris Blackwell was at his house at 56 Hope Road, where Bob later lived. It was a musical conversation. His interest was in the music, he had records piled up to the ceiling. We listened to music he had and talked about the music we would develop together, a crossover of pop and R&B. I liked it.

TONY PRATT [ENGINEER]: Chris had hatched this idea of merging reggae with rock, to appeal to FM-listening rock audiences. Accessibility was important; I think that’s the view Bob took. Bob was already in charge. He was the focal point, with his special charm and personality. His ability to tell a story was very special.

BARRETT: Bob was the leader. My memories of recording the album are of a togetherness vibe. The singers would write songs along with input from the musicians. We smoked a little herb and drink Red Label wine, got the vibes while we laid the tracks down. My favourite is “Rock It Baby”, one of the newer songs we did.

PRATT: Bob arrived in London with the tapes and we started from that point. They were on eight-track, a couple on four-track, so we dubbed them up to 16-track and kept recording. There were vocals that Bob wanted to do again, and keys player ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick played a big part. When Wayne Perkins came in, he struggled with the beat. We were trying to put guitar on “Midnight Ravers”. We ran the track a couple of times, then he waved at me to stop and said, “Rabbit, can you tell me where the fuck the one is?!”

FIND THE FULL INTERVIEW FROM UNCUT MARCH 2019/TAKE 262 IN THE ARCHIVE