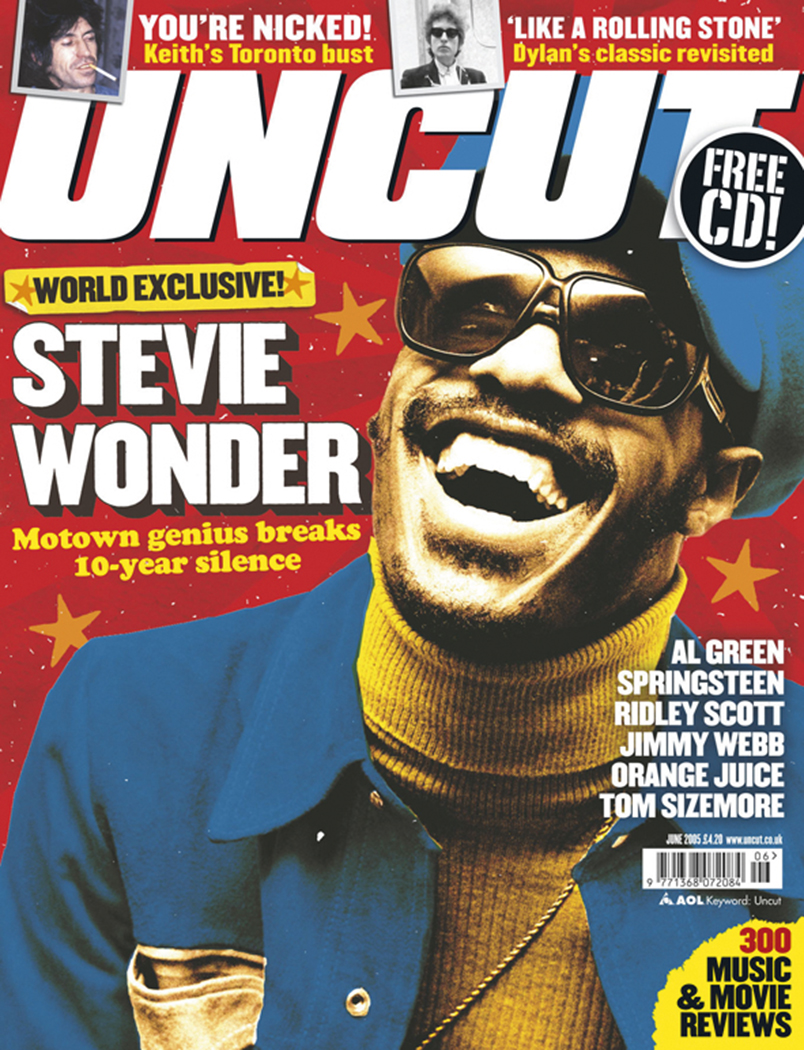

From Uncut's June 2005 issue (Take 97). In a world exclusive interview, Uncut visited the soul legend in his studio as he worked on his then-upcoming album, A Time 2 Love...

Subscription Required!

Subscribe to Uncut+ to get access to our special members area where you’ll find every issue of Uncut stretching back to Take 1 in 1997 plus a comprehensive collection of our Ultimate Music Guides and other special editions. Browse issues from our archive in full and use our search engine to hunt down features and reviews in Uncut about your favourite artists

If you are already subscribe to Uncut+ or the print edition of Uncut magazine, simply login below.

Login

Don't have an subscription?

From Uncut’s June 2005 issue (Take 97). In a world exclusive interview, Uncut visited the soul legend in his studio as he worked on his then-upcoming album, A Time 2 Love…

By the small hours of Saturday morning, L.A.’s Koreatown district is hushed and still. The odd car rattles along Western Avenue, but most of the Friday nightclubbers have dispersed and headed home. “Little Seoul”, if one can call it that, is slowing down.

Unbeknownst to the few locals still awake, the soul legend once known as Little Stevie Wonder is hard at work in the studio that sits slap-bang in the midst of this improbable neighbourhood where few signs or billboards are in English. The blind genius who recorded at least five of the most remarkable albums in the history of American music is rounding off another night behind the massive SSL console of Wonderland, putting finishing touches to a track from his forthcoming A Time 2 Love.

Wonder at work is everything you might imagine. His head sways from side to side as he mumbles melodiously along to “Please Don’t Hurt My Baby“, the track he’s working on tonight. The famous gums of his open smiling mouth show above his upper teeth. His braided hair is bunched behind him, tiny seashells dangling at its ends. He’s dressed entirely in black that matches his sunglasses.

A TV monitor above the console shows a group of women wearing denim and corn-rows and standing round a microphone lowered from the ceiling. The most senior of them, Shirley Brewer, has sung with Stevie since 1972’s Talking Book; hers is the hollering voice that comes in halfway through ‘Ordinary Pain’ on his 1976 masterpiece Songs In The Key Of Life. Like the others, Shirley is trying to master an idiosyncratic vocal line that involves compressing ten syllables into approximately two seconds. Wonder makes the women repeat the line again and again – not like some punishing tyrant, just like a producer who hears each misplaced micro-nuance and needs to hear it done right. He demonstrates it to them once again, semi-scatting the line into their headphones. Eventually they get it down, sensuously purring the line “Before you were usin’ it like a toy” in a way that makes all too plain what “it” is.

Wonder is like a kid brother around these women. It’s not hard to imagine the 12-year-old Little Stevie on the buses that took the famed Motown Revue around America in the early ’60s – the pint-sized japester who’d steal up behind Diana Ross and pinch her petite derriere. He strolls over to one of the singers and extracts a packet of Frito-Lays from her pocket. Before inserting one into his mouth he lifts it to his nose. “Oooh, smell like dirty feet,” he says in the voice of a Mississippi cotton-picker. “Smell like Uncle Charlie’s feets…” The ladies squeal with delighted displeasure. He repeats the phrase several more times and then gobbles down the Frito-Lay.

Wonderland is a hermetic haven of a studio. The family of employees that Stevie has created around him makes for an atmosphere that’s insular but always friendly. Even the security guys are teddy bears. Laughs come thick and fast here, and one of the most infectious belongs to bassist Nathan Watts, who has played with Wonder for 30 years. “I should be in The Guinness Book of Records for longest-serving bass player,” he says. It’s Watts’ birthday today, which is why he’s hanging around long after his services were last required, putting off the long drive back to his home in Chino Hills.

Stephanie Andrews, president of Stevie’s production company, is also sitting in tonight. A tiny woman with a pretty, light-skinned face, she has bought an ice-cream birthday cake for Watts, whose cuddly physique – squeezed into a pair of high-waisted denim shorts – suggests such treats aren’t exactly strangers to his diet. Wonder himself packs a fair paunch under his loose shirt as he emerges to join the impromptu party, which inevitably entails the rendition of ‘Happy Birthday’, his jubilant 1980 tribute to assassinated civil rights leader Martin Luther King.

When the cake has been devoured, Wonder challenges one of the singers to a game of air hockey on a table that sits in the studio’s main recreation room. Despite not being able to see the plastic puck, Stevie repeatedly wins the game, demonstrating what he would doubtless call his Taurean need to triumph at all costs. Then it’s time to go back to work.

“We’re trying to stay in the realm of getting things happening at a reasonable time of day,” Wonder replies when asked if his sessions always run this late. “Sometimes we do work long hours, but very rarely do we work and sleep here for a whole week.”

It turns out that music has reverberated inside these walls for several decades. Back in the ’40s, Wonderland was McGregor’s, a studio used by Benny Goodman, Nat ‘King’ Cole and others. The interior of the building is like something out of Roman Polanski‘s Chinatown, with intricate tiling and wood panels.

When you wander round the back of the studio, outside the bubble-like chamber of the control room, you stumble on relics from Wonder’s own past. Standing alone and somewhat neglected is the original Moog synthesizer he used on Music Of My Mind, Talking Book and Innervisions. Around the corner from that magnificent creature, draped in black cloth, is the Yamaha “Dream Machine” he used on Songs In The Key Of Life.

At the risk of fetishising technology, there is a certain awe in beholding these outmoded dinosaurs. So significant was the role Moog and Yamaha played in the radical brilliance of Wonder’s run of masterpieces from Music (1972) to Songs (1976) that one feels like prostrating oneself before such superannuated devices.

“I’m always intrigued by his orchestral use of synthesizers,” said jazz giant Herbie Hancock, who played on Songs In The Key Of Life‘s impassioned “As”. “He lets them be what they are – something that’s not acoustic.” Listening to the almost classical arrangements of songs such as ‘Pastime Paradise‘ and ‘Village Ghetto Land‘, one appreciates what Hancock meant: it’s as if Wonder is celebrating the very artifice of synthetic sound.

“I think everything has its own character,” Stevie says. “Even in sampling strings, a keyboard player cannot really play like a string player. You can have various samples at various places on the keyboard to accentuate a feel and give you a sense of that, but the whole purpose of me using synthesizers was to make a statement and to express myself musically – to come as close as possible to what those instruments could do, but also to expressing how I would allow those things to sound.”

Wonder’s discovery of electronics was just part of the extraordinary burst of creativity that flowered when he came of age in 1971, ten years after signing as a pint-sized prodigy to Berry Gordy‘s emerging Motown label. In a frenetic four-year run he left “Little Stevie” and the ’60s behind and became one of the towering artists of the new decade.

Imagine black American music without “Superwoman“, “Superstition“, “Too High“, “Living For The City“, “Higher Ground“, “You Haven’t Done Nothin’“, “I Wish“, “Sir Duke” or “Pastime Paradise“. Or without “Blame it On the Sun“, “He’s Misstra Know-it-All“, “They Won’t Go When I Go“, “Knocks Me Off My Feet“, “Joy Inside My Tears“. This is a concentrated body of work that stands alongside the best of the Beatles or Brian Wilson and often eclipses even them.

It’s also a body of work in whose shadow Stevie Wonder has lived ever since. The question in 2005 is, will he ever emerge from it?

FIND THE FULL INTERVIEW FROM UNCUT JUNE 2005/TAKE 97 IN THE ARCHIVE